Brexit: Could UK get ‘associate EU citizenship’?

Source: BBC News

Freedom of movement, access to healthcare abroad, voting rights – some fundamental aspects of British life in the EU must be clarified before Brexit happens.

A Luxembourg liberal MEP, Charles Goerens, has proposed offering British citizens the option of retaining their EU citizenship for a fee. This “associate EU citizenship” idea could be part of the Brexit negotiations but it raises all sorts of legal questions.

What is EU citizenship?

The EU treaties say EU citizenship “does not replace national citizenship” but “is additional to it”. So EU citizenship cannot be acquired by giving up UK citizenship.

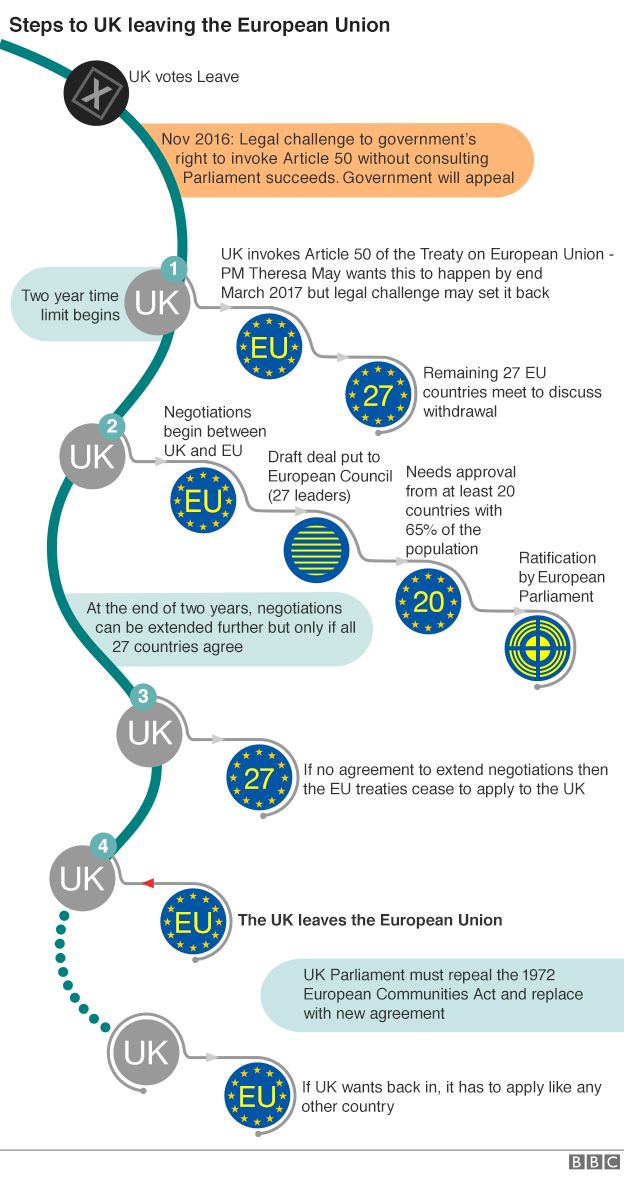

Once the UK leaves the EU, British citizens will lose their EU citizenship. And once Prime Minister Theresa May triggers the Article 50 withdrawal process, which she aims to do before next April, there will be just two years to resolve citizenship issues.

Citizens’ rights have to be part of the Article 50 negotiations because about 1.2 million UK citizens live in other EU countries and three million EU nationals live in the UK. They need to know what, if any, reciprocal rights they will continue to enjoy after Brexit.

Important decisions about jobs, homes, pensions and healthcare could depend on those safeguards.

EU citizenship is described in Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and includes the rights to:

- Travel and live anywhere in the EU

- Vote and stand as a candidate in European and local elections in another EU country

- Get diplomatic protection and consular help from any other EU country in another part of the world.

Beyond those rights, EU law also provides many social protections for EU citizens in the areas of healthcare, work and pensions.

An EU citizen can access another EU country’s social security system, provided he or she has paid social insurance back home. An example is the EHIC health card – a passport to emergency treatment abroad.

The reciprocal rights are called “EU social security coordination”. The rules are complex, as social provision varies greatly from country to country.

How would ‘associate EU citizenship’ work?

Mr Goerens proposes that UK citizens could pay an annual, individual membership fee directly into the EU budget to retain their EU citizenship after Brexit. He did not suggest any figure for that fee.

An associate citizen would retain freedom of movement in the EU, the right to reside in another EU country under existing rules and the right to vote in European elections.

The European Parliament will vote on the proposal next month – it is Amendment 882 in a long report on possible future EU treaty changes.

It has generated much interest on social media and Mr Goerens says many British MEPs have expressed support.

But even if MEPs back the proposal, it still has a long way to go.

What are the obstacles?

The need for treaty change makes this initiative very hard to achieve by the likely 2019 deadline for Brexit.

It could only become law after a treaty change because it would change the nature of EU citizenship.

But aggrieved pro-EU Britons may welcome the fact that Belgian MEP Guy Verhofstadt has backed the proposal.

Mr Verhofstadt, an influential liberal, will be the European Parliament’s lead negotiator on Brexit.

EU leaders will inevitably have to change the treaties in the next few years because the UK’s role will have to be deleted or amended in EU texts.

However, a change to the nature of EU citizenship would require full ratification by all 28 member states – and that could not be done quickly, Prof Catherine Barnard, an expert on EU law, told the BBC.

But the proposal, she said, at least showed a willingness in the EU to “find creative ways to help the 48% who voted to Remain [in the EU]”.

Camino Mortera-Martinez, an EU justice expert at the Centre for European Reform, said there was “no appetite for treaty change in Brussels at the moment”.

Next year politicians in the Netherlands, France and Germany will focus on general elections. They will want to avoid EU treaty changes, which are notoriously time-consuming and difficult. It took nearly nine years to draft and enact the Lisbon Treaty.

Empowering MEPs to continue representing some UK citizens after Brexit would be another big legal hurdle.

Prof Barnard questioned how an MEP could represent an area where “half the constituents are not even associate EU citizens”. “That is a non-starter,” she said.

If British “associate EU citizens” were to have continued freedom of movement, the UK would have to offer the EU something in return, both experts argue.

But that is very problematic. The Brexit vote on 23 June made curbing immigration from the EU a top priority for Mrs May’s government. Freedom of movement will be one of the thorniest issues.

It would also be hard to get agreement on a fee for EU citizenship, Prof Barnard said. For example Spain, hosting many elderly Britons who use its healthcare system, might demand a high fee.

If it took the form of a new EU tax, it would require extra bureaucrats to collect and allocate the income.

The European Court of Justice would have to oversee associate citizenship – another thorny issue, because the whole idea of Brexit is for the UK to “take back control”. So how could an EU court retain jurisdiction over UK citizens?

And it could be discriminatory to offer associate EU citizenship only to UK citizens. Many Serbs and Turks might also demand it, as they would like to join the EU.